- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was born in Switzerland. After receiving his doctoral degree at age 22, Piaget formally began a career that would have a profound impact on both psychology and education. After working with Alfred Binet, Piaget developed an interest in the intellectual development of children. Based upon his observations, he concluded that children were not less intelligent than adults, they simply think differently. Albert Einstein called Piaget's discovery "so simple only a genius could have thought of it."

Piaget (1983) argued that knowledge developed through cognitive structures known as schemas. Schemas are mental representations of the world and how the individual interacts with it. As a child develops, his or her schemas develop as a result of his or her interaction with the world. All children are born with an innate range of schemas, such as a schema for sucking, reaching, and gripping.

These are in

turn modified as a result of experience; Piaget called this process of

modification adaptation. He also argued children actively construct

knowledge themselves as a result of their interaction with new objects and

experiences. For this reason, Piaget is also known as a constructivist. The

child’s interaction with new events and objects as well as the intermingling of

these with existing knowledge cause him or her to develop cognitively.

There

are two types of adaptation.

·

Assimilation –

This process occurs when new events (such as objects, experiences, ideas and

situations) can be fitted into existing schemas of what the child already

understands about the world.

·

Accommodation

– This process occurs when new events do not fit existing schemas. Either a

schema has to be modified to allow the new world view, or a new schema has to

be created. Accommodation is the creation of new knowledge and the rejection or

adaptation of existing schemas.

Adaptation is predicated on the belief that the building of knowledge is a continuous activity of self-construction; as a person interacts with the environment, knowledge is invented and manipulated into cognitive structures. When discrepancies between the environment and mental structures occur, one of two things can happen.

Either the perception of the environment can be changed in order for new information to be matched with existing structures through assimilation, or the cognitive structures themselves can change as a result of the interaction through accommodation. In either case, the individual adapts to his or her environment by way of the interaction.

It is clear that Piaget

believed that cognition is grounded in the interface between mind and

environment. The result of this interplay is the achievement or working toward

a balance between mental schemes and the requirements of the environment. It is

a combination of maturation and actions to achieve equilibration that

advances an individual into a higher developmental stage.

Equilibration

is a mechanism that Piaget proposed to explain how children shift from

one stage of thought to the next. The shift occurs as children

experience cognitive conflict or disequilibrium in trying to understand the

world. Eventually, they resolve the conflict and reach equilibrium of thought.

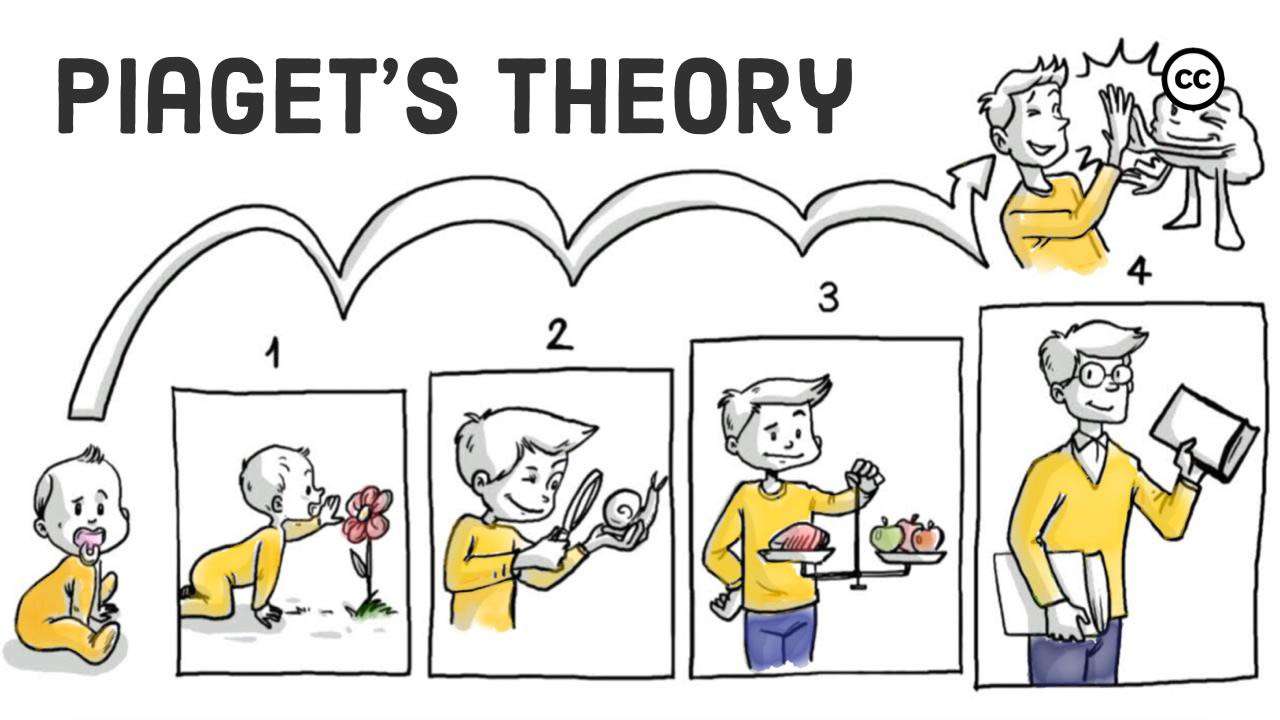

Piaget

then proposed a theory of cognitive development to account or the steps and

sequence of children's intellectual development. He believed that any child

moves through four stages in sequential order during cognitive development and

these are:

SENSORIMOTOR STAGE OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT (0-2 YEARS)

During this

stage, infants and toddlers acquire knowledge through sensory experiences and

manipulating objects. An infant's knowledge of the world is limited

to his or her sensory perceptions and motor activities. Behaviours are limited

.to simple motor responses caused by sensory stimuli. Children use skills and

abilities they were born with (such as looking, sucking, grasping, and

listening) to learn more about the environment. A child at this stage will know

all her family members and try to remember them when he/ she sees them.

According

to Piaget, the development of object permanence is one of the most important

accomplishments at the sensorimotor stage of development. Object permanence is

a child's understanding that objects continue to exist even though they cannot

be seen or heard. Show an orange to a young infant and take it away. A child

will act shocked or startled when the orange reappears. Older infants who

understand object permanence will realise that the person or object continues

to exist even when unseen.

The

Sensorimotor stage can be divided into six separate sub-stages that are

characterized by the development of a new skill.

Phase 1: Reflexive activity (from birth to 1 month)

During the

first month of life, the neonates are totally egocentric beings. There is no

separation between it and its environment. This characterises the sensorimotor

egocentrism, leading to a confusion between the self and the surrounding world.

Also there is lack of understanding that the self is an object in a world of

objects. The major features of this stage are the formation and modification of

early schemes based on reflexes such as sucking, looking, and grasping.

Reflexive activity is also called a period of reflexes. No permanence of

object, no play, no imitation.

Phase 2: Primary circular reactions (from 1-4 months)

Simple motor habits centred on the infant’s own body. Infants start gaining voluntary control over their actions by repeating certain actions that led to satisfying results for example sucking their thumbs. These actions are done randomly. Primary circular reactions are characterised by repetition of behaviours that produce interesting results discovered on infant’s own body and are motivated by basic needs.

During this stage, infants begin to vary their behaviour in

response to the environment and can anticipate events. For instance, a baby of

3 months old is likely to stop crying as soon as his mother moves towards the

crib. This event signals that feeding time is near. There is no permanence of

object and the beginning of playful exercise of schemes. Infants begin to

imitate by copying another person’s behaviour.

Phase 3: Secondary circular reactions (4-8 months)

Between 4 and 8 months, infants sit up and become skilled at reaching far, grasping and manipulating objects. These motor achievements play a major role in turning a baby’s attention toward the environment. The interesting result discovered randomly when the infant is manipulating objects is kept. Infants try to repeat interesting sights and sounds that are caused by their own actions, not on their body but on the external environment.

A child of this sub-stage will

continue to play with a spoon on a plate since it produces an enjoyable noise.

These actions permit the infant to imitate spontaneously the behaviours of

others but they imitate only those actions they themselves have practised many

times. Infants become able to search for objects that have disappeared from

their view or are partially hidden. This behaviour shows that the child has

started developing the object concept.

Phase 4: Coordination of secondary circular reactions

(8-12 months)

Infants are no longer engaged in simple repetition of actions but acquire the ability to coordinate movements in order to reach a certain goal. By the age of 8 months, infants can engage in intentional, or goal-directed behaviour. If for example you show to him/her an exciting toy and then hide it under a cover, he/she can find the object. He/she can retrieve a hidden object from the first location in which it is hidden. He/she will thus be coordinating the scheme of pushing aside the obstacle and grasping the toy.

This means-end action is regarded as

the first truly intelligent behaviour and fundamental for all later problem-solving. The infant’s reaction shows also that for him/her, the object

continues to exist even when he does not see it. He/she has acquired the

concept of object permanence. The child can imitate slightly an action he has

not performed.

Phase 5: Tertiary circular reactions (12-18 months)

The

circular reactions become experimental and creative. The infant repeats an

action with variation aiming to provoke new outcomes. Tertiary circular

reactions consist of attempting actively all the possible means of an action in

order to discover the consequences of actions like “what will happen if I do it

this way?” Psychologists call this stage “discovering new means through active

experimentation”. The child explores the properties of objects by acting on

them in novel ways. Having for example, observed the relationship between a

mate and a toy, the child will pull the mate so that he/she can take the toy.

For the object permanence, the child has got the ability to search in different

locations for a hidden object. Children are able to imitate unfamiliar

behaviours.

Phase 6: Mental representation (18 months to 2 years)

The last

phase of the sensorimotor stage is also called “inventing new means through

mental combinations”. It involves the ability to make a mental

representation that is the internal images of absent objects and past events.

With the capacity to represent, children understand that objects can move or be

moved when they are absent. Representation also brings capacity for deferred

imitation that is, the ability to remember and copy the behaviour of absent

models.

PREOPERATIONAL STAGE OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT (2 — 7 YEARS)

At this

stage, children learn through pretend play but still struggle with logic and

taking other people’s view. Language development is one of the hallmarks of

this period. Piaget noted that children in this stage do not yet understand

concrete logic, cannot mentally manipulate information, and are unable to take

the point of view of other people, which he termed egocentrism.

At this

stage, children also become increasingly adept at using symbols, as evidenced

by the increase in playing and pretending! For example, a child is able to use

an object to represent something else, such as pretending a broom is a horse, a

dog or a cat. Role playing also becomes important during the preoperational

stage. Children often play the roles of "mommy," "daddy,"

"doctor" and many other characters.

Moreover,

in this stage, a child’s ability to represent experiences mentally rather than

to interact with them directly and physically is developed. The ability to

represent the world with words, images and drawings is manifested. A child’s

representational ability at this stage shows the appearance of pre -operational

intelligence, which still lacks a system of rules or mental operations as shown

by older children and adults. Consequently, the thinking of young children is

unsystematic, inconsistent, illogical, disorganised and often confused. This

implies that the pre-schooler who can symbolically represent the world would

still lack the capability to perform operations.

CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT (7 - 11 YEARS)

At this

point of development, children begin to think more logically about concrete

events but have difficulty understanding abstract or hypothetical concepts.

Logically,

Piaget determined that children in the concrete operational stage were fairly

good at the use of inductive logic. Inductive logic involves going from a

specific experience to a general principle. On the other hand, children at this

age have difficulty using deductive logic, which involves using a general

principle to determine the outcome of a specific event.

The signs

of operational thinking starts to show when children are ready to go to school

at the age of 6 or 7 after preoperational thought gradually disappear. This is

the stage of concrete operations because children

are able to perform operations and logical reasoning replaces intuitive

thoughts. Logical operations that may be manifested include dealing with

principles of formal logic or mathematical concepts of space and time. The

development of concrete operations allows children to engage in a form of

thinking which is flexible and reversible

unlike in the preoperational stage. For instance concrete operational thinkers

cannot imagine the steps required to solve an algebraic problem, which is too

abstract for thinking at this stage of development.

The

concrete operational period in Piaget's theory represents a transition between

the preoperational and formal operational stages. Whereas the preoperational

child does not yet possess the structures necessary to reverse operations, the

concrete operational child's logic allows him or her to do such operations, but

only on a concrete level. The child is now a sociocentric (as opposed to

egocentric) being who is aware that others have their own perspectives on the

world and that those perspectives are different from the child's own. The concrete

operational child may not be aware, however, of the content of others'

perspectives (this awareness comes during the next stage of cognitive

development).

THE FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE

The formal

operational stage begins at the onset of adolescence and lasts through

adulthood. The formal operational stage is the fourth and final stage of

Piaget's theory of cognitive development. This stage involves an increase in

logic, the ability to use deductive reasoning, and an understanding of abstract

ideas. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract

concepts. Skills such as logical thought, deductive reasoning, and systematic

planning also emerge during this stage.

Piaget

believed that deductive logic becomes important during the formal operational

stage. Deductive logic requires the ability to use a general principle to

determine a specific outcome. This type of thinking involves hypothetical

situations and is often required in science and mathematics.

While

children tend to think very concretely and specifically in earlier stages, the

ability to think about abstract concepts emerges during the formal operational

stage. Instead of relying solely on previous experiences, children begin to

consider possible outcomes and consequences of actions. This type of thinking

is important in long-term planning.

In this

stage which is associated with adolescents, individuals move beyond the world

of actual, concrete experiences and think in abstract and more logical terms.

For instance, they may imagine what a caring parent is like and then compare

their parents with the imagined standard. They start to entertain possibilities

for the future and get fascinated with what they can be. Formal operational

thinkers are more systematic, develop hypothesis about why some events occur,

the way they do and finally test the concerned hypotheses in a deductive

fashion in solving problems that they encounter.

Piaget’s

stages are holistic; logically organised wholes (complete) schemata. They are

hierarchical, more less like a stair case. Each successive stage incorporates

the elements of the previous stage. What is added today incorporates what we

already have and what is contained in the next stage is qualitatively

different. Each stage is distinctively different.

SUPPORT AND CRITICISM OF PIAGET'S STAGE THEORY

Piaget's

theory of cognitive develop is well-known within the fields of psychology and

education, but it has also been the subject of considerable criticism. While

presented in a series of progressive stages, even Piaget believed that

development does not always follow such a smooth and predictable path. In spite

of the criticism, the theory has had a considerable impact on our understanding

of child development. Piaget's observation that kids actually think differently

than adults helped usher in a new era of research on the mental development of

children.

THE PIAGET’s THEORY'S IMPACT ON EDUCATION

Piaget's

focus on qualitative development had an important impact on education. While

Piaget did not specifically apply his theory in this way, many educational

programs are now built upon the belief that children should be taught at the

level for which they are developmentally prepared. In addition to this, a

number of instructional strategies have been derived from Piaget's work.

These

strategies include providing a supportive environment, utilising social

interactions and peer teaching, and helping children see fallacies and

inconsistencies in their thinking.

While there

are few strict Piagetians around today, most people can appreciate Piaget's

influence and legacy. His work generated interest in child development and had

an enormous impact on the future of education and developmental psychology.

EVALUATION OF PIAGET’S THEORY

Positive criticism

·

Piaget

produced the first comprehensive theory of child cognitive development.

·

He

modified the theory to take account of criticism and envisaged it constantly

changing as new evidence came to light.

·

A

great deal of criticism has been levelled at the ‘ages and stages’ part of his theory but it is important to

remember the theory is biologically based and demonstrates the child as a

determined, dynamic thinker, anxious to achieve coherence and test theories.

·

Piaget

was the first to investigate whether biological maturation drove cognitivedevelopment and his vision of a child having cognitive changes regulated by

biology is now widely accepted and supported by cross-cultural research.

·

He

also developed the notion of constructivism – he argued children are

actively engaged with constructing their knowledge of the world rather than

acting as passive receivers of information. This now widely accepted idea

changed the view of childhood and significantly influenced the education

profession.

Negative criticism

·

Piaget’s

methods have been criticised as too formal for children. When the methods are

changed to show more ‘human sense’, children often understand what is being

asked of them and show cognitive ability outside of their age appropriate

stage. The small sample sizes also mean caution should be used then

generalising to large groups and cultures.

·

He

failed to distinguish between competence (what a child is capable of doing) and

performance (what a child can show when given a particular task). When tasks were

altered, performance (and therefore competence) was affected.

·

The

notion of biological readiness has also been questioned. If a child’s cognitive

development is driven solely by innate factors, then training would not be able

to propel the child onto the next stage.

·

Piaget

has been criticized for under-estimating the role of language in cognitive

development.

·

He

has also been criticized for under-estimating the role of social development in

cognitive development. The ‘three mountain experiment’ is a presentation of a

social scene and yet Piaget focused on it solely as an abstract mental problem.

·

The

theory is very descriptive but it does not provide a detailed explanation for

the stages. Piaget’s supporters would suggest that, given his broad genetic explanations,

the technology did not exist for him to research his assumptions in depth.

· The model can be seen as too rigid and inflexible. However, its supporters argue that Piaget never intended it to be seen in such a light, and it should be seen more as a metaphor and a guiding principle for teaching and learning.

Comments

Post a Comment