- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

High intelligence level in human makes them different from other creatures. It helps them to cope with complex situations of everyday life. The level of intellectual capacity differs from one individual to another and will determine how they will succeed in various activities they decide or are asked to undertake. It will also determine the performance in schools, the quality of decisions they make as well as the efficiency at work.

These benefits of

intelligence arouse interest of organisations such as schools or any other

business institutions in predicting the level of achievement of people in any

activities and where their services will be needed. It is for this reason a

highly controversial but very much beneficial intelligence quotient (IQ) test

was developed. A numerical value or score of intelligence that is obtained from

this test is based on the ratio between the people's mental age and

chronological age. This section will focus on different ways of measuring

intelligence.

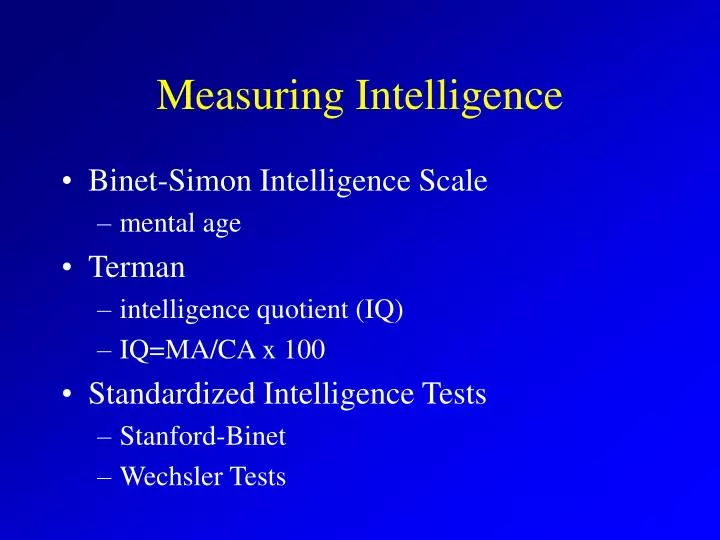

9.1.1 THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTELLIGENCE TESTS

The idea of measuring intelligence began in 1904 in France, when the psychologist Alfred Binet was commissioned by the French government to find a method that would assist to differentiate between children who were ‘intellectually normal’ and those who were ‘inferior’ (slow learners). This was intended to put the latter into special schools where they would receive more individual attention. This would help the government to avoid the disruption they caused in the education of intellectually normal children.

Such thinking was a natural development from

Darwinism and Eugenic Movement that dates back to Sir Francis Galton in 1869,

the famous scientific polymath who promoted the idea that for the society to

prosper, the weakest should not have babies, as this would affect the genetic

stock of future generations. He and his followers were contemptuous of any

impact education might have on raising the achievement of the ‘least able’ .

Since,

according to Binet, intelligence could not be described by a single score, the

use of the intelligence quotient (IQ) as coined by Lewis, M. Terman in America

in 1916, as a definite statement of a child’s intellectual capacity would be a

serious mistake. In addition, Binet feared that IQ measurement would be used to

condemn a child to a permanent condition of stupidity, thereby negatively

affecting his/ her education and likelihood.

Despite such concerns,

psychometric tools use in learning institutions and work places gained a

significant momentum and in the various countries of the world. These tools

have been revised and modernised and typically include tests such as the

revised versions of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale or WAIS – R for 18

years old people and above; the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children or

WISC – III for children aged 6 to 17 ; the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale

of Intelligence or WPPSI for children 4 to 6 1/2 years old (Kasschau, 2003), and the British

Ability Scale or BAS in their updated forms but their roots and core constructs

remain unaltered.

9.1.2

The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale

Binet’s intelligence test has been revised

many times since he developed it. In the United States of America, Binet's test was

refined by Lewis Terman of Stanford University into a test called

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale. The Stanford-Binet, like the original test, groups test

items by age level. To stimulate and maintain the child’s interest, several

tasks are included, ranging from defining words to drawing pictures and

explaining events in daily life. Children are tested one at a time. Examiners

must carry out standardised instructions while putting the child at ease,

getting him to pay attention, and encouraging him to try as hard as he can.

Intelligence tests such as

these are used to predict how people will perform in situations or tasks that

seem to require intelligence like in school or on the job. Scores on

intelligence tests (IQ tests) indicate whether an individual has correctly

answered as many questions as the average person of his/her own age.

The IQ, or intelligence

quotient, defined as a measure of a person's intelligence as indicated by an

intelligence test is the ratio of a person's mental age (the

average age of those who also received the same score as that child) to their chronological age(actual)

multiplied by 100.

• For instance, if a Childs MA is 10 years and his CA is also 10 years, then his IQ is 100 (10/10× 100=100).

• IQs that

are over 100 (high IQ) show that the person is more intelligent than the

average person of his own age (the mental age is greater than the chronological

age). Example: if a Childs MA is 10 years and the CA is 8 years, then his IQ is

10/8 x100=125.

• IQs which

are less than 100 (lower IQ) indicate that the individual is less intelligent

than the average person of his own age (the mental age is lower than the

chronological age. For example, if a child's CA is 12 years and the MA is 9 years,

then his IQ is 9/12x100=75.

• Scores on

IQ tests indicate whether an individual has correctly answered as many

questions as the average person of his/her own age.

So an 8-year-old child who scored at the mental age of 8 would have an IQ of 100. Although the basic principles behind the calculation of IQ remain, scores are figured in a slightly different manner today. Researchers assign a score of 100 to the average performance at any given age. Then, IQ values are assigned to all the other test scores for this age group. If you have an IQ of 100, for example, this means that 50 per cent of the test takers who are your age performed worse than you.

In addition, test scores for several abilities are now reported

instead of one general score. Most learning institutions have done away with

this type of test; It was replaced by the Otis-Lennon Ability Test which seeks

to measure the cognitive abilities that are related to a student’s ability to

learn and succeed in school. It does this by assessing a student’s verbal and

nonverbal reasoning abilities.

Three frequently

used intelligence tests are the revised versions of the Wechsler-Adult

Intelligence Scale, or WAIS-R (Wechsler, 1981), for adults; the Wechsler

Intelligence Scale for Children, or WISC-III (Wechsler, 1981), for children 6

to 16 years old; and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of

Intelligences, or WPPSI-R, for children 4 to 61⁄2 years old.

In addition to

yielding one overall score, the Wechsler tests yield percentile scores in

several areas, namely vocabulary, information, arithmetic, picture arrangement,

and so on as shown in the example of the Wechsler Tests below.

These ratings are used to compute separate IQ scores for verbal and performance abilities. This type of scoring provides a more detailed picture of the individual’s strengths and weaknesses than a single score does.

In most Wechsler

Intelligence Scales, the test items shown above are included although we did not

show all possible items. I am sure most of you have seen similar items in

Special Paper 2 of the End of Grade 7 National Examination in Zambia.

9.1.4 THE USES AND MEANING OF IQ SCORES

In general, the norms for intelligence tests are

established in such a way that most people score near 100. This means that about 95 percent of people score

between 70 and 130. The norms are illustrated in the following Gaussian Curve.

|

| This normal curve displays intelligence as measured by IQ tests. Copyrighted to the owner |

As indicated on the curve, only a little more than 2 percent score at or above 130. These people are in at least the 97th percentile. Those who score below 70 have traditionally been classified as mentally handicapped. More specific categories include mildly handicapped, but educable (55–69); moderately handicapped, but trainable (40–54); severely handicapped (25–39); and profoundly handicapped (below 25).

IQ scores seem to be most

useful when related to school achievement; they are quite accurate in

predicting which people will do well in schools, colleges, and universities.

Critics of IQ testing do not question this predictive ability.

The question however remains,

whether such tests actually measure intelligence. Although most psychologists

agree that intelligence is the ability to acquire new ideas and new behaviour

and to adapt to new situations. Generally, IQ tests measure the ability to

solve certain types of problems. Yet they do not directly measure the ability

to pose those problems or to question the validity of problems posed by others (Hoffman, 1962). This is only part of the reason why IQ testing is so controversial.

CONTROVERSY OVER IQ TESTING

Much of the debate about IQ

testing centres around the following issues: do genetic differences or

environmental inequalities cause two people to receive different scores on

intelligence tests? The question of cultural bias in intelligence tests has

also been controversial.

1.

Nature vs. Nurture

A technique researchers use to

help determine whether genetics or environment affects scores on intelligence

tests is studying the results of testing of people with varying degrees of

genetic relationship. In regard to intelligence, researchers have found a high

degree of heritability or a measure of the degree to which a

characteristic is related to inherited genetic factors. They found that as

genetic relationship increases, say, from parent and child to identical twins,

the similarity of IQ also increases.

The best way to study the

effects of nature and nurture is to study identical twins who have been

separated at birth and raised in different environments. The study of more than

100 sets of twins who were raised apart from one another revealed that IQ is

affected by genetic factors. This finding was supported by the discovery of a

specific gene for human intelligence. According to some psychologists, 70

percent of IQ variance can be attributed to heredity, but others found the

hereditary estimate to be only 52 percent. This would mean that heredity

and environment almost contribute equally to the person’s intelligence.

In this Regard, studies on

environmental factors show that brothers and/or sisters raised in the same

environment are more likely to have similar IQs than siblings raised apart.

Environment, therefore, does impact IQs.

Some studies show that quality

preschool programs for example, help raise IQs initially, but the increase

begins to fade after some years. Participating children, however, are less

likely to be in special education classes, less likely to be held back, and

more likely to graduate from high school than are children without such

preschool experiences. Each year of school

missed may drop a person’s IQ as much as 5 points. The richness of

the home environment, the quality of food, and the number of brothers and

sisters in the family all affect IQ.

Both heredity and environment

have an impact on intelligence. Advances in behavioural genetics research

continue to refine results on the contributions that heredity and experience

have on IQ. It remains clear that these two factors are both contributing and

interact in their effects.

2.

Cultural Bias

A major criticism of

intelligence tests is that they have a cultural bias that is, the

wording used in questions may be more familiar to people of one social group

than to another group. For example, on one intelligence test the correct

response to the question, “What would you do if you were sent to buy a loaf of

bread and the grocer said he did not have any more?” was “try another store.” A

significant proportion of minority students, however, responded that they would

go home. When questioned about the answer, many explained that there was no

other store in their neighbourhood.

Psychologists admit that some

tests have been biased because they assess accumulated knowledge, which is

dependent on a child’s environment and opportunities in that environment. As a

consequence, efforts have been made to make the tests less biased. However, it

is unlikely that a test will ever be developed that will be completely free of

cultural bias. All tests are based on the assumptions of a particular culture.

An example of the culture bound test is shown below

This is a test developed by a psychologist, Adrian Dove in 1960 to demonstrate how one’s cultural background can affect their performance in an intelligence test.

Comments

Post a Comment