- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Moral Development or development of morality is the process whereby children learn to consciously distinguish right from wrong. During early childhood, a sense of morality is born when children realise that certain behavioural patterns are regarded as good and sometimes rewarded by parents. On the other hand, some actions are considered to be bad and are frequently accompanied by punishment. As children become older, morality begins to involve a complex set of ideas, values, and beliefs.

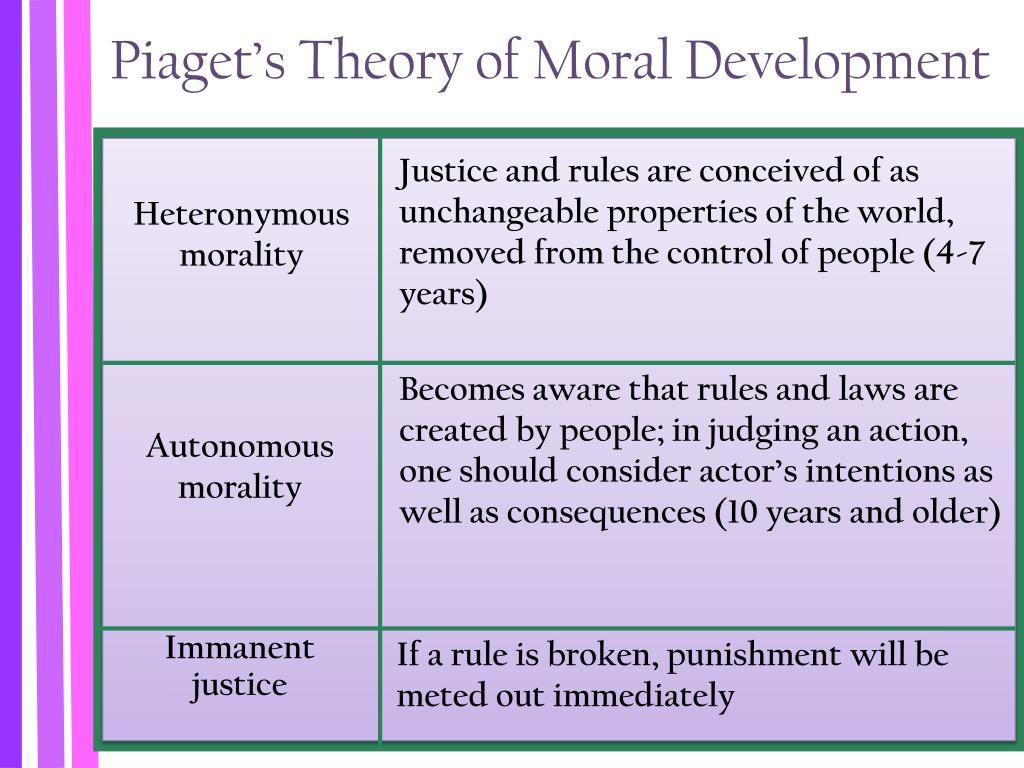

But his most important observations were made on the boys a fact that incurred later criticism, as will be seen shortly. Piaget often used a practiced technique of feigned naivety: He pretended to be ignorant of the rules of the games and asked the children to explain them to him. In this way he was able to comprehend the way that the children themselves understood the rules, and to observe as well how children of different ages related to the rules and the game. He came up with two main stages of moral development as follows:.

Heteronomous morality, or moral realism (5 to 10 years)

The word

heteronomous means under the authority of another. As the term suggests,

children of this stage view rules as stipulated by significant others (parents,

teachers as well as God), as having a permanent existence, unchanged and

requiring strict obedience.

During and

before early school years, children have little understanding of rules that

govern social behaviour. When they play rule-oriented games, for example, they

do not mind about wining, losing, or coordinating their actions with those of

others.

At the age

of 5, they start to show much more concern with and respect for rules.

According to Piaget, two factors limit children’s moral understanding:

•

The power of adults to insist that children comply,

which promotes unquestioning respect for rules and those who enforce them.

•

Egocentrism. Children think that all people view rules

in the same way, their moral understanding is characterised by realism. That

is, they consider rules to be permanent and features of reality rather than as

subjective principles that can be modified at will.

Children of the heteronomous stage believe in immanent justice- that

wrong doing inevitably leads to punishment. They think that moral order is only

maintained by punishment.

This stage is divided into three components or sub-stages according to

the child’s achievement in terms of morality developmental level.

-

In the first sub-stage, in which the child

merely handles the marbles in terms of his/her existing motor schemes, the

child’s Play is purely an individual endeavour, and “one can talk only of motor

rules and not of truly collective rules.

-

In the second sub-stage, about ages four to seven, game playing is

egocentric; children do not understand rules very well, or they make them up as

they go along. There is neither a strong sense of cooperation nor of

competition. It is equally important to note that egocentric children at the

preoperational stage seem to have “collective

monologues” rather than true dialogs, these observations do not seem

surprising.

-

The third sub-stage, at about ages seven to ten or eleven,

is characterised by incipient cooperation. Interactions are more social, and

rules are mastered and observed. Social interactions become more formalised as

regards rules of the game. The child learns and understands both cooperative

and competitive behaviour. But one child’s understanding of rules may still

differ from the next, thus mutual understanding still tends to be incomplete.

2. Autonomous morality or The Morality of Cooperation (about 10 years and above)

This is Piaget’s

second stage of moral development, in which children view rules as flexible,

socially agreed-on principles that can be revised to suit the will of the

majority. Children at this stage cease to regard unquestioning obedience to

adults as a sound basis for moral action. They recognise that sometimes there

may be justifiable reasons to violate or change a rule. Also, they discard the

view that wrongdoing is inevitably punishable. Instead, punishment should be

rationally related to the offence.

In this stage, beginning at about age eleven

or twelve, cooperation is more earnest and the child comes to understand

rules in a more legalistic fashion. Furthermore, Piaget calls this the stage of

genuine cooperation in which

the older children show a kind of legalistic fascination with the rules. They

enjoy settling differences of opinion concerning the rules, inventing new

rules, and elaborating on them. They even try to anticipate all the possible

contingencies that may arise. But in terms of cognitive development this stage

overlaps Piaget’s formal operational

stage; thus here the concern with abstraction and possibility enters the

child’s imagination.

Children’s Moral Judgments

Piaget’s studies of moral

judgments are based both on children’s judgments of moral scenarios and on

their interactions in game playing. In terms of moral judgments, Piaget found

that younger children (around ages four to seven) thought in terms of moral realism or moral heteronomy. These terms

connote an absolutism, in which morality is seen in terms of rules that are

fixed and unchangeable (heteronomy means “from without”). Guilt is determined

by the extent of violation of rules rather than by intention.

Comments

Post a Comment